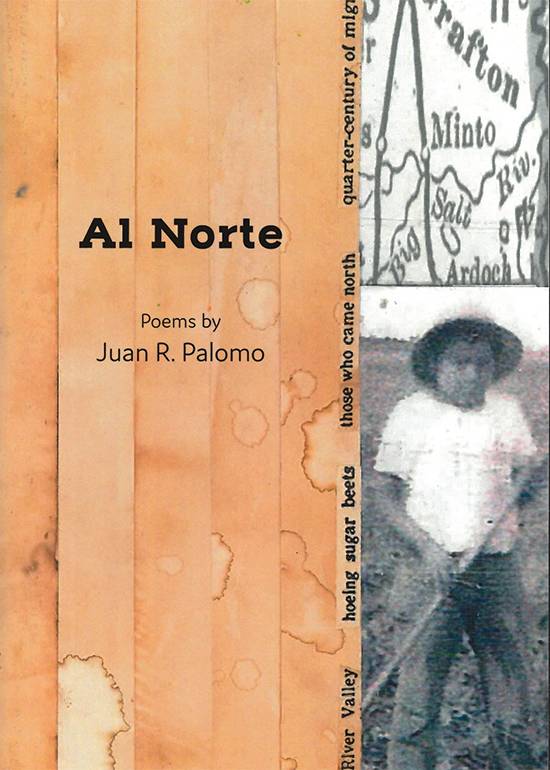

Al Norte

by Juan R. Palomo

San Antonio: Alabrava Press, 2021.

42 pp. $15 paperback.

Reviewed by

Cloud Delfina Cardona

“Al Norte is not a spectacle of pain and suffering, but rather an ode to Tejano families like his, that bonded together in the midst of doing what they needed to do to survive.”

Due to webpage formatting issues, the quoted poetry in this review does not always have the same spacing or indention as it originally appears in print.

Juan R. Palomo’s Al Norte traverses the speaker’s memories of his family going Al Norte, a reference to North Dakota where his family participated in migrant work. Al Norte is a road trip that takes readers through the realities of northern migrant camps, childhood observations, and a few Tex-Mex detours. Palomo does not romanticize his family’s struggle to survive as migrant workers but rather, he portrays a nuanced reality—moments of their pain, joy, and everything in between.

In the second poem of Al Norte, “Impermanence,” Palomo guides readers through the threshold where we follow his family from Crystal City, Texas, into North Dakota. “Impermanence” is the first poem that presents Palomo’s playful language and alliteration, which is found throughout Al Norte. “Impermanence” illustrates the family’s pit stops for “bags full of burgers” and the sounds of the road, “taca-ta-taca of tires ticking off / concrete squares coaxed me to sleep.” His use of alliteration brings lightness to these heavy moments. What matters more than the exact locations in this book is his togetherness with his family. He says this in the poem,

Each time I asked, “¿Dónde estamos?”

But it didn’t matter where we were.

What I really sought/yearned for was

The reassurance of a familiar voice.

Throughout Al Norte, Palomo weaves in the racial anxieties and struggles his family confronted against the backdrop of the fields. For example, in “Pepineros,” the poem has an omniscient point of view with a focus on the speaker’s mother. His mother notices the inequalities her family experiences in comparison to the other families nearby. The speaker says:

Their shack is no more than a mile from the shores

of Green Lake, yet she finds it hard to ignore

the distance between her family and those passing by

on the two-land road. They are a sun-worshiping

migratory tribe, she thinks, these visitors from Chicago,

Milwaukee, and other distant cities. They travel

in chilled cars and spend their days and nights in the cool lake

and cooled cabins.

The speaker’s mother notices all of these class differences, juxtaposing her children’s long sleeves and wide-brimmed hats for protection to these visiting families in their swimsuits. The end of the poem has a ladder out of this unfairness and sorrow, seeking out the positive from this situation. The mother thinks:

Maybe, like snakes shedding skin,

they need to leave their innocence behind to become

toughened to the cruelty of a world ruled by other tribes.

Palomo doesn’t paint his memories of field work with feelings of despair or admiration, he portrays the complex reality of what it was like for his family to work in the fields. His honesty allows for exploration of his family’s fear of deportation, which is seen in “The Only Thing We Have To Fear” and “The Day They Do Not Show Up.” Palomo’s honesty also allows for moments of humor in the midst of these traumatic moments. In “The Only Thing We Have To Fear,” the speaker describes officers that approach his parents, asking them about their legal status, to which they reply, “The sheepish response: born in Mexico, in this country since 1920.” In the Chicano tradition of teasing loved ones, the speaker notes, “the humor slowly emerged, with people joking about / each other’s reactions and answers and who acted more scared.”

Weaved throughout Al Norte are moments and reflections outside of the fieldwork. Memories of ESL classes in “Cruzando My Own River” and a speculative moment in “Las Virgenes” where the speaker remembers going to the movies with La Virgen de San Juan del Valle, his madrina, where “La Virgen went unnoticed / until the lights dimmed and her halo / began to glow in the darkened theater.” “Speed Queen, North Dakota,” the final poem of Al Norte, is part elegy, catalog, and celebration. The speaker returns to the migrant camp where his family spent many summers. He says:

Like an abandoned tombstone,

the Speed Queen assures me, yes,

here there was once life. A summer

community existed. Families

interacted.

Juan R. Palomo leaves readers with his catalog of memories in this last poem, like mothers who brought their newborns from the hospital to the camp and kegs of Hamm’s Beer and cheese enchiladas. Just as the speaker ends the poem with picking up a lump of coal that he slips into his pocket, readers also leave this chapbook with Palomo’s migrant memories—all of the joy, pain, heartache, and bonding lumped into one. This is what Al Norte succeeds at best: braiding the harsh reality of fieldwork and sentimental moments of a Mexican-American childhood. Al Norte is not a spectacle of pain and suffering, but rather an ode to Tejano families like his, that bonded together in the midst of doing what they needed to do to survive.

Cloud Delfina Cardona is an illustrator, poet, and educator from San Antonio. The author of What Remains, winner of the 2020 Host Publications Chapbook Award, Cloud Delfina Cardona is also the co-founder of Chifladazine and Infrarrealista Review.