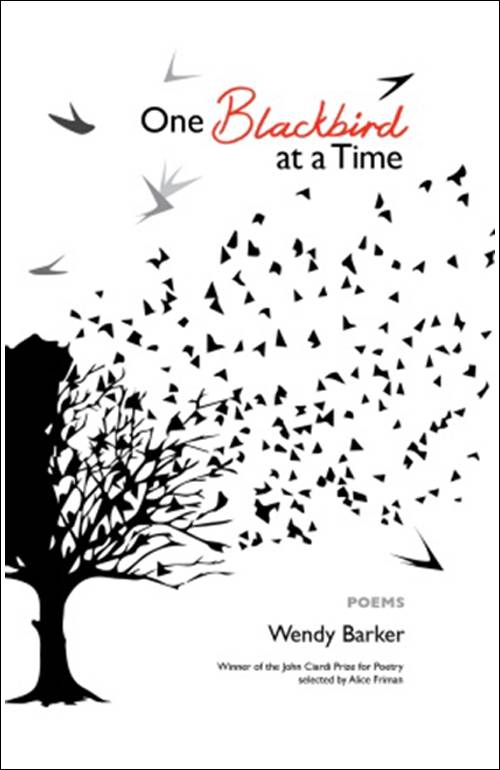

One Blackbird at a Time

by Wendy Barker

Kansas City: BkMk Press, 2015

78 pp. $13.95 paper

Reviewed by

Sarah Cortez

“The rewards offered by this volume are elegant rejoinders to the oft-spoken truism among English faculty: if you teach, you can’t do your own writing. Yet these poems of Barker’s workplace (“endless air-conditioning,” “closet of a seminar room”) show us what can happen when the poet brings her sensibility and sharp eye (as well as gorgeous diction) to that locus known as “the daily grind.””

Reading Wendy Barker’s One Blackbird at a Time, winner of the John Ciardi Prize for Poetry, is a sheer pleasure. Each poem is written as a meditative response to Barker’s thirty-five plus years of college classroom experience teaching literature and creative writing. Her light but exact touch reveals a deftness that only a master could accomplish through the stitching of personal history with the wise, as well as often dense, observations and quips by students. The ostensible thread used in this “stitching” is the wealth of novels, essays, poems, and epics studied in the classroom under Barker’s hand.

The rewards offered by this volume are elegant rejoinders to the oft-spoken truism among English faculty: if you teach, you can’t do your own writing. In fact, which lecturer and professor doesn’t complain of the writing time and energy sapped by heavy teaching loads and endless committee work? Yet these poems of Barker’s workplace (“endless air-conditioning,” “closet of a seminar room”) show us what can happen when the poet brings her sensibility and sharp eye (as well as gorgeous diction) to that locus known as “the daily grind.”

One of the reasons for the poems’ appeal is the generosity with which Barker has shared her own self, as deconstructed into many “selves.” An early failed marriage, youthful fears, moments of haunting failure—all are mentioned in important ways at exact moments that illumine the reader’s understanding of the past, but also, and most importantly, illumine the reader’s understanding of the poet’s chosen vocation, the teaching of literature and creative writing as a university professor in today’s fractured and fracturing world.

This book is divided into five sections with the first containing only one poem, "I Hate Telling People I Teach English.” This clever choice establishes both the poet’s stance toward her material and invites the reader into a world where actions and dialogue are utterly unpredictable and where preposterous things happen. Those who teach writing and/or those who long to write and be published will find themselves shivering with delight (or embarrassment) as Barker’s gentle humor and sense of the absurd envelop both sides of the equation. Section two takes us into the classroom and into Barker’s life. These poems touch both realms of the American classroom with Barker’s signature lightness and all-encompassing gentle, ironic humor.

At the beginning of the third section, the book’s tone shifts in the introductory poem about teaching Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” an initially lighter poem that turns and unbalances the reader with the ache of life’s losses. In Barker’s own words, “so at first we hear lightheartedness,/a witty irony—but then the sounds grow/vaster, catch us off guard. And quicken.”

This section, in each successive poem, brings into consideration accidental (and tragic) death, the inscrutability of modern urban life, prejudice, war, existential loneliness, and ends with a longer meditation on the destructive nature of family dynamics. At times, these explorations find the students’ quoted responses dry as a desert that must be trudged through, gritty and interminable. At times, the students’ quoted responses are the vital, life-giving oasis. The stability and sureness of the poet’s polite voice coupled with her own self-questioning allows the students to speak plainly, to be themselves, while affording that same intoxicating freedom to the poet.

Section Four begins with “Whenever We’ve Dipped into Walden,” a poem that builds on the hints about Barker’s family history by looking at a series of bodies of water. This gives us a perfectly timed series of revelations into the adroit art of the poet’s craft as she unspools and then rewinds the meanings of Thoreau’s work. The graceful ending note of the poem: “the lake where water is always leaving to become air” is almost as life-sustaining as a welcomed breath of forest air—clean, invigorating, wholesome.

The section continues with poems about teaching literature woven with the buried histories, memories, and reflections from and about the past skewing gradually toward conclusions—the ending of a difficult marriage, the end of life, and the end of the poet herself. All of these are thoughts the poet has prepared her reader to consider. Thus, the effect is one of hearing a dear friend speak the truth without the luxury of self-pity or the slyness of hidden agendas. The poet’s honesty has already made us her friend.

This friendship carries us into the final part. It is a profoundly moving episode with its many threads of loss and of being lost, of paths forged and roads neglected or abandoned, and, finally, of the professor’s love and need for the students and the bonds that have flourished in only a semester’s time through the exploration of literature together.

The final poem, “The Last Time I Taught Robert Frost,” is a quiet piece of love and a deeper ache of haunting paralysis as the poet looks back to the day before her own father’s death. She recalls the power of a poem by John Masefield recited aloud to a dying father and the inescapable memory of a Frost poem that she couldn’t voice a few moments later. The poet then recounts her intuitive maneuver as she asks her students, years later, to recite the Frost poem together with her. This deep and soul-filling connection between the students and the teacher is one of the most beautifully rendered in the book. This final moment is the poet’s last gift to us. It is wrapped in a wide, blue satin ribbon, so that we may carry it home with us safely intact:

I can’t explain it, but for once

something dark and deep entered among us in the overly

air-conditioned room. As if we were all one self and yet still alone

in the cold, and wanting to stay. When we spoke again,

we talked until I had to stand up, open the door, and tell them

to leave, say it was past time for their dinners and

all the lovely, nagging promises waiting for them to keep.

Sarah Cortez is a councilor of the Texas Institute of Letters and winner of the PEN Texas Literary Award in Poetry. She is an award-winning anthologist and writer with hundreds of publications worldwide. Her latest anthology is Goodbye, Mexico: Poems of Remembrance (Texas Review Press, 2015), already an award-winning book.