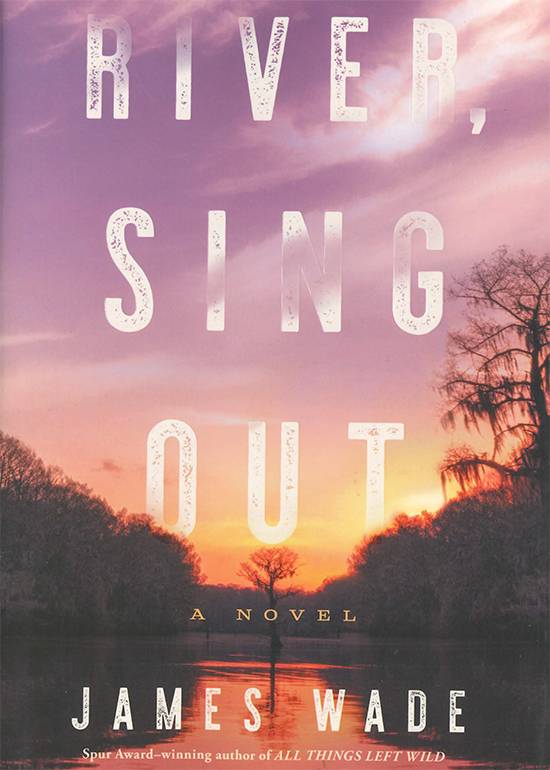

River, Sing Out

by James Wade

Ashland: Blackstone Publishing, 2021.

275pp. $27.99 hardcover.

Reviewed by

Chisom C. Obike

“Wade’s novel captures moments of darkness with lush and enthralling language, setting up a stark contrast that leaves the readers with feelings of dissonance to pair with the happenings of the novel. ”

If you enjoy scenic word-painted images or novels that beg you to think about the place of humanity, then I suggest you read Wade’s River, Sing Out. Featuring a style akin to Cormac McCarthy’s, Wade’s novel captures moments of darkness with lush and enthralling language, setting up a stark contrast that leaves the readers with feelings of dissonance to pair with the happenings of the novel. River, Sing Out invokes an ominous sense of eerie silence, gravity, and darkness.

The narrative of River, Sing Out focuses on the adventure of a boy, Jonah Hargrove, and a meth-addicted teenage girl, River, who stumbles upon his porch with thousands of dollars’ worth of stolen meth. Each with their personal motives—Jonah seeking to escape his abusive father and the cyclical poverty of his hometown, and River seeking to get away from her drug-filled life in East Texas—the unlikely pair embarks on a coming-of-age odyssey. Similar to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, River, Sing Out’s protagonists find themselves on a journey guided by a body of water as they challenge their understandings of life and themselves. This simultaneously occurs as a local drug lord, John Curtis, and his cronies try to find River and reclaim the drugs she stole. All this plays against the backdrop of the novel making claims about man’s impact on the Earth and invoking nature’s retaliation through a silent and omniscient Thin Man who holds that “what we name evil is in truth just consequence, the result of things…spooled out over the histories of men.”

It is no wonder this novel is praised for its skillfully executed lyrical prose, because it is well-deserving of it. Wade utilizes lyrical elements to house the juxtaposition of darker and heavier scenarios with visually pleasing and brighter ideas. Holding the light and dark together, Wade creates a sense of an even darker tone for the novel’s narrative as opposed to making light of an already intense moment. An example of this can be seen in Wade’s detailing of River running away with the stolen meth, “she zipped the backpack and began to walk on raw and bloodied feet as the first drops of rain fell from the swollen clouds.” The way Wade uses this element is one factor of the book’s beauty and power.

Wade’s voice is one of the novel’s greatest strengths because it not only characterizes the novel, but it also contributes to characterizing the part of East Texas that Jonah and River attempt to flee from. By using lyrical prose to juxtapose elements of light and dark, Wade immediately makes it clear to see the depravity in the dark elements of the narrative’s occurrences as he describes them in tandem with the light elements of his scenic and visually romantic writing. In other words, the presence of the light elements underscores the intensity of the darker ones. The dissonance revealed by this juxtaposition is what goes towards giving this novel the same ominous and eerie tone. An example of this can be seen in how Wade relays an instance where Cade injects himself to get high. In that moment, Cade “leaned against the window as the dome light went from bright to Holy. His eyes avoided the glow and focused instead on the rain drops as they fell on the windshield like a growing pox.” The binary opposition throughout emphases the themes of good, evil, and the nature of man.

However, for as much as this novel succeeds in the earlier mentioned stylistic and formal element, it suffers elsewhere. One clumsy element is the of depicting different characters’ simultaneous perspectives of an event; think of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. Such a style of writing is tricky to execute because it easily confuses readers. It is jarring to come across a scene one has already read, but from the perspective of a different character. And the novel’s arrangement only deepens the confusion. As opposed to giving each character’s perspective of an event one after the other, the novel spreads them out, intermingling these perspectives with the continuance of other parts. The choice to do this may have been made to prioritize the thematic flow of the novel, but it must be noted that it also affects the reading experience.

Nonetheless, James Wade’s River, Sing Out deserves the accolades it has garnered thus far. You may find yourself having to turn pages back and forth to figure out how the events are connected or who says what, but when you make it through the novel, you will find that your time was well spent.

Chisom C. Obike is a graduate student in the MA Literature program at Texas State University, San Marcos.