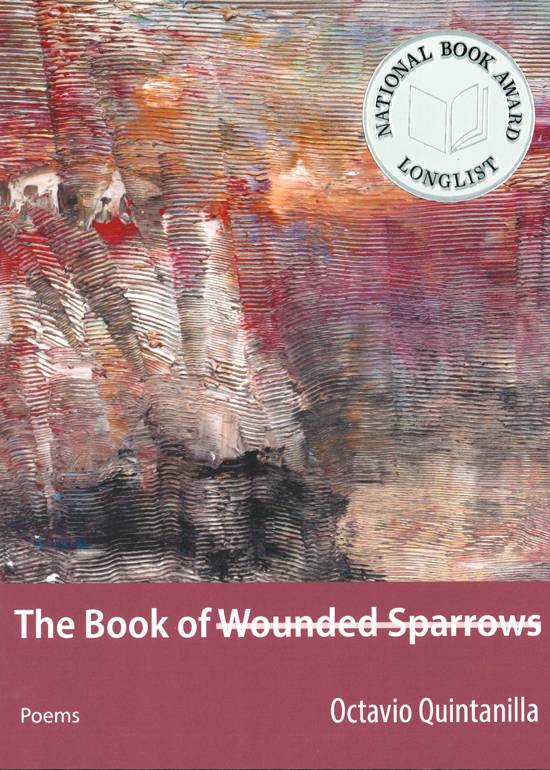

The Book of Wounded Sparrows

by Octavio Quintanilla

Huntsville: Texas Review Press, 2024.

122 pp. $21.95 Paperback.

Reviewed by

Victoria Garcia

“Some people write about South Texas and Mexico in a broad and stereotypical way, but this collection does not feel like that at all. There are poems about how painful disconnection caused by being separated from a parent as a child and poems about love and masculinity. These poems connect to South Texas through nature or by telling a story only some people know.”

In his second full-length poetry collection, Octavio Quintanilla connects the fragments of his childhood after his migrating to South Texas from Mexico. The tone of the book is set by opening with a photo of a handwritten Mother’s Day card dedicated to the poet’s parents. This photo is accompanied by the poem “A Mother’s Day Card,” “A Mother’s Day card is all I have to remind me/ that, once, I was child:/ Red hearts on yellowish paper, torn edges.”

Other poems approach topics, such as being a child in a new country, learning a new language, forgetting your family and mother tongue, the complexity of the American Dream and questioning your identity, but each poem is entirely original, either through diction or form.

The book is split into three parts and each section ends with a selection of visual art, which Quintanilla dubs his “Frontextos” that range from colorful abstract to line art. The poems follow a range of forms from short lines, “To cross/ a river/ without/ your parents/ is to feel/ a tree/ drowning/ in your/ chest.” As well as including poems with longer sentences, “I am writing and I am thinking about what I write.” The assortment of poems also includes prose, which introduces a different tone but slowed down my reading and gave me a break from poetic form. Quintanilla does a lovely job of describing childhood memories in vivid detail, “Be a boy again and watch/ your mother strangle/ a chicken to feed you.” The book is littered with narrative poems each telling a part of a fascinating journey.

The poems play with different forms. Some poems utilize left margin alignment while others are set on the right margin. Some poems that take the entire page with complex sentences, and it’s interesting to see Quintanilla use up the white space of a page. The collection as a whole, poems and art pieces alike, make a statement about being unafraid to make the page one’s own. The collection experiments with punctuation, with some poems containing proper grammar, “Sometimes, weeks go by, and I don’t call my mother. Sometimes a month goes by and a sign on the side of the road reminds me to call her,” while other poems abandon punctuation completely by utilizing line breaks. As a reader, this was a key aspect that kept me engaged with the content of the book from start to end.

The book also contains sequences of poems, one example is titled, “Postscript.” This is a longer set of poems separated by star symbols and are written in second person. Only the last two out of the six poems are titled, “(Mother) 1” and “(Mother) 2,” and these poems explore what it means to learn to live in a new language. Quintanilla brings in details such as writing to tell this story, what it means to sacrifice a new language for another, “Two lexicons bordered by constants: English is never enough. Spanish is never enough. Language is never enough, and yet, it is the only home you truly know.” Quintanilla scatters his love for the written word throughout the poem, with poems dedicated to poetic lines and metaphors, “Line & Metaphor (1)” and “Line & Metaphor (2),” but also through the titles of his other poems such as “Essay on Loss,” “The Poetics of Separation: A Micro-Essay,” “Letters to the Afternoon,” and "Writing a Poem is Almost like Climbing a Tree." These poems alone add tangible details to the collection as a whole.

As someone from the same area in South Texas as Quintanilla, I personally felt connected to the themes in the collection, and I enjoyed how the poems felt personal. I could picture the stories told through the poems. In the poem “Migrations,” Quintanilla writes, “When my father lost his memory,/ he went on remembering he was lost./ I’m in a desert, he said./ Now I’m in a river.” This story of memory loss is a familiar concept, but Quintanilla has a way of expanding on just one story by bringing in aspects such as nature. This poem ends with these two sentences, “The ceiling fan cut into pieces like cake/ by the streetlights. The strange woman/ leaning close, watching him sleep.”

Some people write about South Texas and Mexico in a broad and stereotypical way, but this collection does not feel like that at all. There are poems about how painful disconnection caused by being separated from a parent as a child and poems about love and masculinity. These poems connect to South Texas through nature or by telling a story only some people know. Despite my personal connection to this book, I don’t think a reader needs to be personally familiar with the concepts of migration or learning and forgetting a language to connect to these poems. At the core, these poems are about migration and growing up, but they offer more than that through visual poetic art, the descriptive language, and creative storytelling. The raw emotions and honesty in the poems will capture the attention of any reader.

Victoria Garcia is a first-year MFA poetry student at Texas State University.