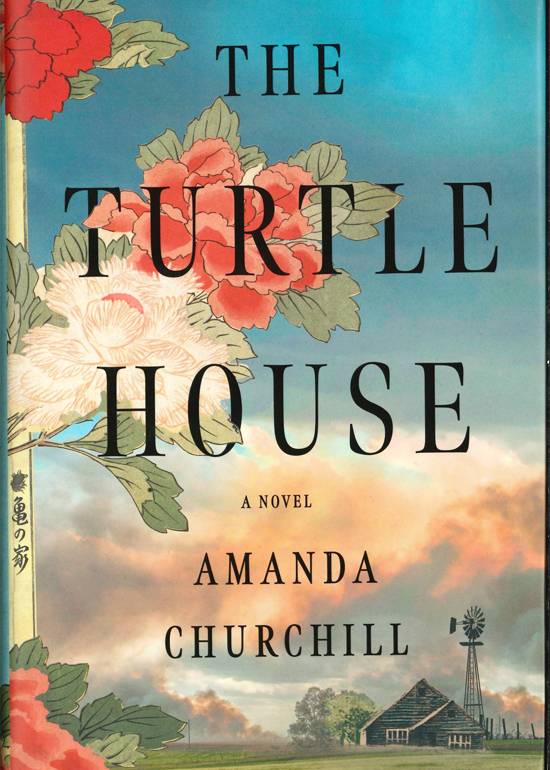

The Turtle House: A Novel

by Amanda Churchill

New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2024.

296 pp. $30 Hardcover.

Reviewed by

Jeehyun Lim

“Amanda Churchill’s novel offers an opportunity to think about the literary representation of Asian Americans in Texas by offering readers the story of a young Japanese woman, Mineko, who marries a small-minded and mean American GI and relocates to her husband’s hometown, Curtain, Texas, in the mid-twentieth century.”

According to a 2023 report published by Asian Texans for Justice, there are approximately two million Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders living in Texas. They make up 6.6% of the state population, which may not seem like a lot, but they are a rapidly growing population. In terms of the yearly growth of the Asian population between 2022 and 2023, the report claims Texas saw the largest increase of any state in the union. If statistics like these are often the basis of advocating for political representation, Amanda Churchill’s novel offers an opportunity to think about the literary representation of Asian Americans in Texas by offering readers the story of a young Japanese woman, Mineko, who marries a small-minded and mean American GI and relocates to her husband’s hometown, Curtain, Texas, in the mid-twentieth century. The novel, however, is not only Mineko’s story but also about her granddaughter, Lia Cope, a twenty-five-year-old woman who has to take a break from her budding career as an architect due to the sexual harassment she experiences from her former architecture professor. Organizationally, The Turtle House moves back and forth between the first-person perspective of Lia in 1999 and the third-person perspective of Mineko’s story from 1936 to 1999. The interweaving of the two temporalities and perspectives has many benefits for the novel. It develops the relationship between the grandmother and the granddaughter, which is at the heart of the novel’s view on the legacy of Mineko’s immigration; it also encompasses more than half a century into the roughly monthlong time in which the narrative unfolds, imbuing the novel with both historical scope and contemporaneity.

Two themes worth noting in Churchill’s beautifully written novel: home and women’s struggles. The novel opens with the seventy-three-year-old Mineko’s displacement after she accidentally burns down the house she was living in, the house left to her after James’s death. Both Mineko and Lia are temporarily housed in Lia’s parents’ house. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that both need to build their own homes. Churchill’s novel prompts readers to think about what home is and what it means from multiple angles. Mineko’s homesickness may seem similar to tropes of nostalgia common to literature of immigration, yet in The Turtle House home is not just a place of birth but also a place one actively makes. The home Mineko misses is not the house of her childhood but the abandoned kominkan, or the traditional-style Japanese house, she discovered and shared with her beloved Akio. This is the titular turtle house and Mineko’s home. When Mineko moves to the United States, Curtain, Texas, is at first an unwelcoming place, a place where she is a “Jap” and where she often experiences petty racism. Slowly, incrementally, Mineko creates a home for herself in Curtain. Her quest to rebuild the turtle house is the culmination of Mineko’s efforts to root herself, to find a true home in her adopted country. The support and help Lia provide her grandmother in this process is an illustration of her architectural training at the University of Texas at Austin being put to good use. It is also what gives the readers hope that Lia may recover from her professional setback and find herself as an architect.

Lia’s deepening understanding of her grandmother is based on her own struggles as a woman. Just as Mineko endures James’s petty, everyday acts of cruelty, Lia struggles with sexual harassment by Darren, a serial sexual predator who abuses his position of power and privilege. Lia’s context of sexual exploitation is different from that of Mineko’s who had to work in a military camptown in US-occupied Japan. On the cusp of the twenty-first century in Austin, Texas, young women have more and better avenues of employment and financial independence than military prostitution. Yet these women still remain vulnerable to sexual predation and gender discrimination in areas of society where power is concentrated on elite networks of men. Mineko’s memories of her first and true love, Akio, who dies in World War II, not only sustains her but also serves as hope for Lia that an authentic romantic relationship exists.

The Turtle House is a fine example of Asian American literature from the South, a field that is becoming more recognizable. In an early chapter in the novel, Mineko and Akio have a conversation in the turtle house about beauty. At a time of rapid change and modernization, the kominkan is a style of architecture going out of fashion, Mineko says. “But this place was built as Kadoma was,” she adds, “and so I think that one day it might be of use to the town.” This statement captures well what appears to be Churchill’s outlook on art and the matrix from which it is born. The Turtle House is a novel built out of the Japanese American experience in Texas. Not only is it beautiful, but it is also made well, just like the turtle house. It is sure to find an audience that gives it the recognition and affection it deserves.

Jeehyun Lim is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin. She specializes in Asian American literature and culture and US ethnic literature.