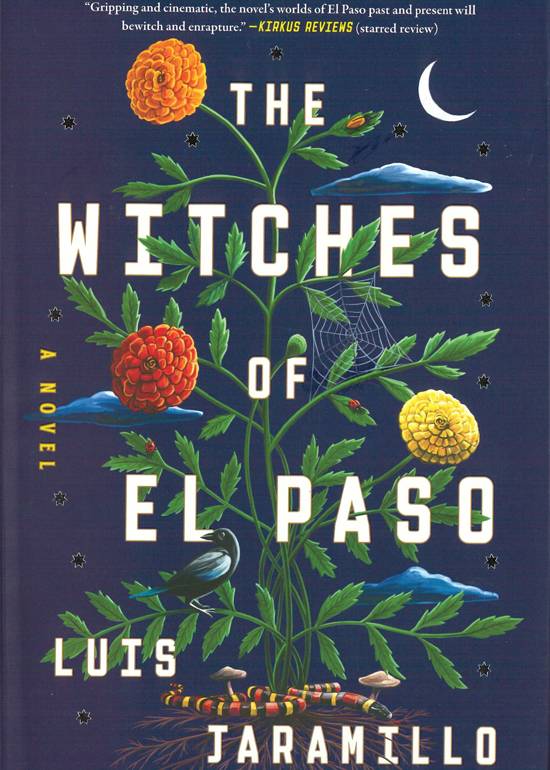

The Witches of El Paso

by Luis Jaramillo

New York: Primero Sueño Press, 2024.

275 pages, $27.99 Hardcover.

Reviewed by

Kathleen Morrish

“The Witches of El Paso introduces vivid and memorable elements of magic. The book begins with small hints of power that grow in ways that emphasize the senses and the appetites of Marta, a middle-aged lawyer, and Nena, her great aunt.”

In his debut novel, Witches of El Paso, Luis Jaramillo returns to familiar topics of his short story collection, The Doctor’s Wife, crafting a multi-generational tale focused on key moments in the lives of two women. But, unlike his stories, The Witches of El Paso introduces vivid and memorable elements of magic. The book begins with small hints of power that grow in ways that emphasize the senses and the appetites of Marta, a middle-aged lawyer, and Nena, her great aunt. The reader learns that this power, called La Vista, cannot be controlled. While La Vista will sometimes work in harmony with the bruja, or witch, who channels it, it “isn’t a tool, it’s a force. An energy that enters you and uses you.” A bruja pays for daring to wield La Vista to her advantage.

As the power that allows brujas to travel between the present and the past, La Vista serves as a powerful metaphor for borders of time and space. A border isn’t a line in the sand; it’s a space in its own right that asserts its power on the people adjacent to it, bringing both opportunity and danger. Marta and Nena live on both the border between the United States and Mexico and the border between past and present. These borders shape every aspect of their lives.

In an interview with Erinrose Mager for Bomb, Jaramillo states, “I called [the protagonist of The Doctor’s Wife] The Doctor’s Wife because I wanted her to be placed in this confining role. Cleaning, cooking for the kids, running the house: these acts are confining.” In The Witches of El Paso, Jaramillo puts Marta into the same confining role, casting her husband as a doctor. Jaramillo further constrains the women through the social limitations imposed on them by their culture. In Marta’s case, she serves at a small law firm serving under-privliged Latinas, in part because “The path to a federal judgeship was not made for women, especially not for Latinas.” In the young Nena’s case, she’s trapped living with her working sisters and caring for their children while their husbands are fighting in World War II. But the women sometimes overcome their limitations easily. For example, Marta manages to have plenty of free time to help Nena reunite with her daughter despite having two children, a frequently absent husband, and a challenging job.

Jaramillo’s creative power is at its finest during the magical climax, where the young Nena channel the power of La Vista to create a brebaje, a stew that confers closeness to La Vista. She inadvertently calls hundreds of animals to sacrifice themselves. At the height of the scene, the reader sees this in action: “Nena crouched down, the animals crawling over her, claws and toes and hooves trampling her to get to the pot, the room filling with the tangy odor of fresh meat, the musty stink of boiled fur.” The scene’s description transports the reader into a memorable, otherworldly setting.

Readers will notice Jaramillo’s knack for using food and cooking to establish a sense of the cultural landscape of the story and how the characters fit into it. For instance, he portrays the childhood version of Nena helping her mother make pozole to sell to make ends meet. She and her sister “made the soup, soaking the hominy in lye to better slip the skins off the kernels, wringing the chickens’ necks and plucking them.” In contrast, as a young woman in the home of Don Javier, she is presented with fine meals by servants. She describes one such meal: “The little meatballs were delicious, served in a light tomato sauce. Next came lomo with carrots and potatoes, and then after that, coffee, with figs.” Nena is entranced with the richness and variety of dishes served in the Javier household.

The book deals with the realities of differential power between classes. Ruminating on her case against Soto, Marta thinks “Soto can afford to hire the best attorney in El Paso, get her case dismissed with a flick of his wrist. This is what money and influence buys, the ability to evade justice.” Yet Marta continues to fight for the rights of her poor clients, hoping she can bring together enough people and power, magical and otherwise, to overcome Soto’s advantage. In today’s political environment, many people find themselves in positions similar to Marta’s, struggling against power and money for justice. This book offers them a timely and welcome message of hope.

Kathleen Morrish (she/her) has sung with choirs in the Royal Albert Hall, Tchaikovsky Concert Hall, and Carnegie Hall; attained a Ph.D. in applied mathematics; worked as a computer scientist; served as a tabloid reporter in Second Life for Axel Springer SE; and had her creative work published in The Fib Review and elsewhere. She serves as Fiction Editor for Porter House Review and is a second-year fiction candidate in Texas State University’s Creative Writing MFA program.