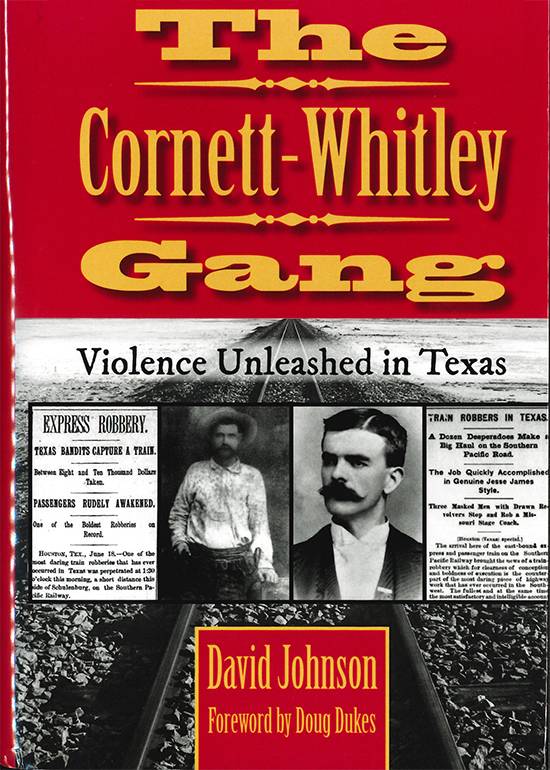

The Cornett-Whitley Gang:

Violence Unleashed in Texas

by David Johnson

Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2019.

284 pp. $29.95 Hardcover.

Reviewed by

Joseph Fox

“Here Johnson charts the short-lived operations of a gang of East Texas train robbers, the lawmen tasked with bringing them to justice, and the press that sensationalized the story every step of the way.”

Train robbers hold a place in the mind America’s western storytellers as daring outlaws bold enough to rob what is often seen as a symbol of modernity encroaching on the frontier. Examples abound such as Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 silent-era classic The Great Train Robbery on the escapades of train robbers and their gunfights with lawmen. Complicating simple narratives is The Cornett-Whitely Gang: Violence Unleashed in Texas by Texas historian David Johnson. Here Johnson charts the short-lived operations of a gang of East Texas train robbers, the lawmen tasked with bringing them to justice, and the press that sensationalized the story every step of the way.

The Cornett-Whitley Gang originally met in early 1887 in the mustang pen of a ranch in Karnes County for the purpose of organizing a new money-making venture using violence and intimidation. The gang consisted of younger men who mostly grew up in Texas: Sion Searcy Secrest, Ed Reeves, Bud Powell, Ike Cloud, John Barber, and the namesakes of the gang Bill Whitley and Brack Cornett. After robbing trains at McNeil Station in Williamson County and on a suspension bridge north of Flatonia in Fayette County, the gang incurred the attention of a sensationalist press and the lawmen determined to deliver justice. Due to increased pressure, the gang split in the following year with many members forming new gangs to commit bank robberies and a final attempted train robbery near Harwood in Gonzales County. They were mostly either shot in gunfights with lawmen (like the sociopathic Brack Cornett), double-crossed by their partners (such as Bill Whitley by his “friend” Alfred Y. Allee), or captured outside of the state (such as Bud Powell who tried to restart his life in Montana). Johnson rejects the idea that the gang members were social bandits but instead sees them as greedy outlaws out for their own profit. This gave the gang a “demonic” nature that manifested itself not just in the gratuitous violence of their actions (beating a telegrapher at McNeil Station, firing indiscriminately at trains, and shooting passengers that got in their way) but also what Johnson describes as a curse on everyone with whom they came in contact. Johnson does not come across as superstitious in using the term “curse” but notes a pattern of many lawmen and accomplices involved with the pursuit of the gang also ended up meeting untimely ends. The gang also brought out the worst in prominent Texas newspapers who degraded themselves by misreporting important details of the case, constantly painted law enforcement as not up to the task of catching the gang, and often assumed the guilt of many people who were arrested on suspect evidence. In a final manifestation of the “curse,” the train from the Harwood robbery was hit in 1890 by a waterspout near Del Rio, Texas. Coincidence? The reader can wonder.

While perhaps prone to poetic and literary flourishes, Johnson gets his facts straight by using official records, applying scrutiny to witness testimony, and using genealogical sources to create profiles of the actors in the story. While Johnson is an excellent fact checker, it is easy for a reader to lose track of the central narrative of the story amidst the constant corrections of press accounts or earlier biographers of the gang. In this light, The Cornett-Whitley Gang would greatly benefit from a timeline or map marking the events of the story or key locations. While the gang’s ruthlessness earns Johnson’s description as “demonic,” the reader is left without a broader view of where these outlaws fit into the story of Post-Civil War Texas. Compared with the feuds, racial violence, and wars that marked Texas’s history on the American frontier, the story of the gang does not hold a feather in terms of violence and aggression (as bad as they were). Johnson himself acknowledges this in noting that the train robberies “divert[ed] attention from the infamous San Saba County War, then in full swing, a conflict far more violent than train robberies.” Still, Johnson deserves a tremendous amount of credit for bringing attention to an interesting regional story previously is not well-known outside of East Texas. Despite the violence brought by the gang, Johnson sees a great deal of virtue in the victims who recovered and continued their lives as well as the “Brotherhood of the Badge” made up of lawmen who did not forget about the gang even after press attention waned. The message is clear, while violence leaves a curse which can bring out the worst in people, it can also be overcome.

Joseph Fox is the Associate Education Officer at the Museum of South Texas History in Edinburg, Texas and holds master’s degree in history from Texas State University in San Marcos, Texas. His areas of research include Borderland and Texas Music History. He has written articles for the Handbook of Texas History, a historical marker for the Texas Historical Commission, and completed a Master’s Thesis on the relationship between Lone Star beer and the 1970s Austin music scene.