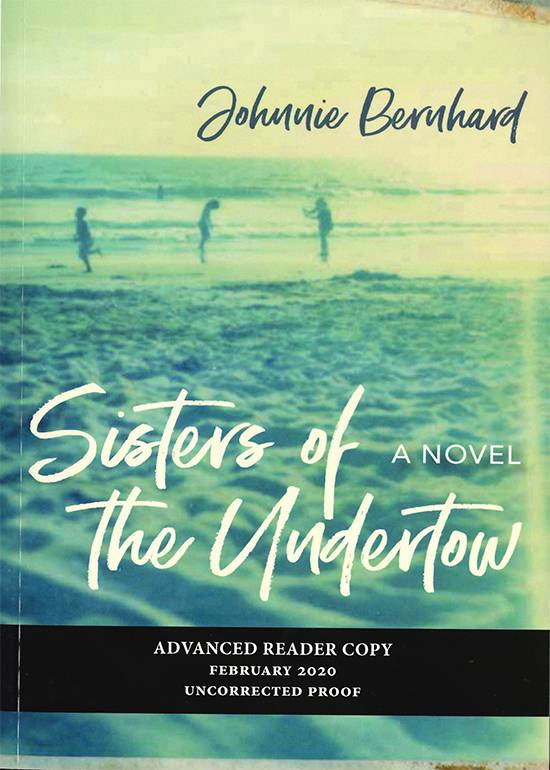

Sisters of the Undertow

by Johnnie Bernhard

Huntsville: Texas Review Press

182 pp. $21.95 Paperback.

Reviewed by

Ana Freeman

“Despite these many flaws, the book’s ending, like its beginning, is sweet. When the long-awaited moment of Kim’s true acceptance of Kathy finally arrives, in the middle of Hurricane Harvey, it is an incredible relief. In these final pages, the characters at last begin to transcend their tired archetypes.”

Johnnie Bernhard’s new novel, Sisters of the Undertow, deals in the perennially relevant theme of jealousy between siblings. But much like its protagonist’s attempts to help homeless patrons of the library she works at by giving them McDonald’s coupons, the book is a good intention, poorly executed. Though Bernhard starts off with a touching premise, her character development proves insufficient to anchor readers amidst so many literal and figurative storms.

Sisters of the Undertow centers on the insufferable Kim; in the tradition of Belle from Beauty and the Beast and Bella from the Twilight series, she’s an effortlessly beautiful, introverted bookworm fancying herself far too sophisticated for her humble Texas surroundings. Because of the broad strokes of this trope, it is hard to find Kim believable, much less sympathetic. We watch Kim grow from childhood to middle age perpetually resentful of the attention given her uncool, disabled sister, Kathy. As Kim builds an increasingly lonely existence (speckled with encounters with a variety of thoroughly abusive men), Kathy, with her ignorant enthusiasm for life and “pure heart,” serves as an equally shallow foil.

Despite her continual cruelty to Kathy, Kim’s desire for a loving relationship with her sister is hammered into the reader with lines such as “I found myself crying, craving the touch of her hand, the warmth of her hug, the sweetness of her love for me.” With foreshadowing as unsubtle as this, it is no spoiler to reveal that Kim eventually learns from her sister’s perpetually innocent way of moving through the world. Kim’s disability, which is never specified, is romanticized and used only to teach the protagonist a lesson. Paralleling this, the characters of color are props to show Kathy’s lack of regard for social norms (she “liked dark men”) and to help Kim learn to accept difference (her black friend compares his race to Kathy’s disability, helping Kim understand it). Bernhard clearly has good intentions with respect to these characters, but falls back on reductive, if positive, stereotypes.

Unfortunately, the problems with this novel don’t stop with the broadly drawn characters and their melodramatic encounters. Sisters of the Undertow skims through vast swaths of Kim’s life using narration instead of scenes, and rarely fails to scream the significance of what’s happening to readers. An early moment when Kim’s family experiences a rare flush of togetherness is almost tender, until we are knocked over the head with it: “I never felt as loved or alive as I did then…I knew without a doubt, I was part of something magical, as large as the universe, this earth. It was my family.” Similarly, when Kathy meets her college boyfriend, Bernhard characterizes him with a textual sledgehammer: “He was special—kind, intelligent, athletic. I didn’t know what box to put him in…Brian lived in a land I was unfamiliar with. I’d never known a boy like him.” In this manner, the book suffers from failing to heed that tried-and-true storytelling mandate to show rather than tell.

Despite these many flaws, the book’s ending, like its beginning, is sweet. When the long-awaited moment of Kim’s true acceptance of Kathy finally arrives, in the middle of Hurricane Harvey, it is an incredible relief. In these final pages, the characters at last begin to transcend their tired archetypes. If readers can imitate Kim in learning to muster the patience and credulity of Kathy, Sisters of the Undertow offers a glimpse of a rainbow at the end of its tedious tempests.

Ana Freeman is a graduate student at Texas State University.