The Watershed Project

by David Norman

San Antonio: Black Rose Writing, 2021.

200 pp. $16.00 paperback.

Reviewed by

Jeranda Dennis

“Overall, Norman has produced a well-written novel that deserves a thorough read to fully absorb its concluding message about toxic religious ideals.”

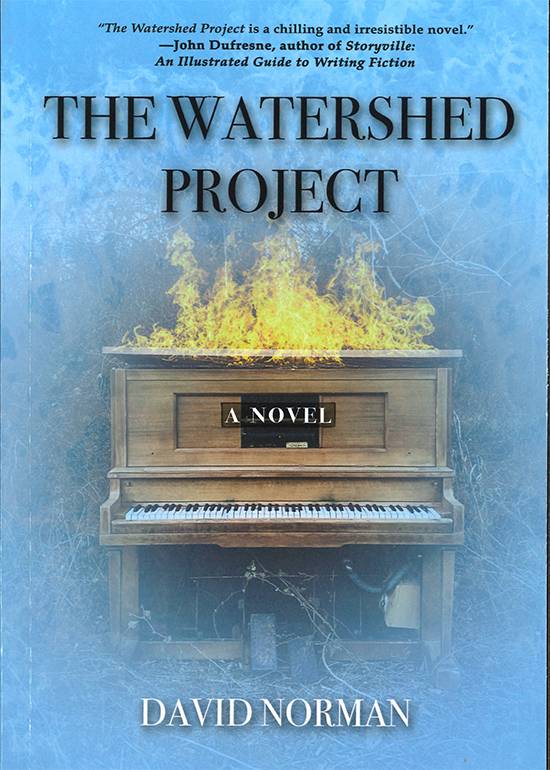

David Norman’s The Watershed Project is a psychological literary novel about a corrupt minister and his broken Central Texas family with a dangerous secret inside their piano in their small church barn. Norman uses the epistolary format to separately delve into the troubled mind of Pastor Zacharias “Zach” Hembrey and his mentally distressed teenage daughter, Elizabeth, as they argue about the truth behind the tragic events that took place at a Saturday night lock-in at their church. Norman also utilizes dark humor and ambiguity to lighten the heavy themes such as familial drama, mental-health, drug-abuse, and most importantly, questionable religious morals.

The book begins with Zach on the radio announcing the details of prior horrific incidences at his church that included a deadly bombing that resulted in the death of his new keyboardist, and his daughter being admitted into a psychiatric institution. Zach is a recovering alcoholic who one day while vacationing in South Padre with his family, religiously “diverted” becoming a born-again Christian then moves his family to Salterra, Texas, to start his own church. His new church (named Watershed Project) is a dilapidated barn at the end of a cul-de-sac, and he “poached” its new members from the San Antonio mega church, which the family previously attended. One night Zach is kidnapped from his home by the infamous drug dealers the Alejandro Brothers and forced to hide their drugs in his church, or they will kill his family. He agrees to this dangerous situation, yet he keeps this secret hidden from his family. This triggers him to relapse into drinking and causes a rift between his daughter and him.

Norman does a great job establishing Zach and Elizabeth as unreliable characters, which causes a perception of ambiguity. Zach is controlling and obsessed with maintaining a self-righteous façade and encourages readers to “form our own opinions” about the events, which makes us question his true motives. However, Elizabeth promises to give the whole truth of the events and remove any “sly redactions” her father may have made. She is depressed about the family’s abrupt move to Salterra and her father’s random decision to start a church, so she is determined to sabotage its success. Therefore, due to the father and daughter’s clashing personalities, readers have no idea who to believe. The book has a compelling and mysterious tone to last page.

As Zach continues to establish his church and hide his secret, Elizabeth grows concerned about the new keyboardist, Fred Valenkemp, calling him a “devil in a black suit” because of his irrational anger towards those that touch his music equipment and the fact that his daughter, Nelly, became friends with Elizabeth and confided in her about his abuse towards her and her mother. Elizabeth also believes he is the cause of her father’s sudden relapse. Unfortunately, Zach repeatedly ignores her concerns and severely declining mental health, which leads her to develop vandalizing, pyromaniac, and self-harming tendencies. Once these behaviors become uncontrollable and can no longer be ignored, her parents finally admit her into a psychiatric institution. Norman excellently uses Elizabeth to touch on the subject of “Preacher’s Kid Syndrome” which is an experience that children of clergymen often have when such strict and high expectations are placed on them. Elizabeth says, “He [Zach] couldn’t have a crazy daughter. He needed a model Christian daughter to make announcements, set up the donuts and coffee, and hand out flyers. He didn’t care about me. All he cared about was his stupid church.” Elizabeth doesn’t believe that her father is trying to help her get well, he only wants to protect the image of the church, so these stressful expectations led to her mental health issues and resulted in her dangerous rebellious actions against her hypocritical father and his religious teachings.

Although the plot is filled with unexpected twists and interesting character decisions that keep its progress steady, there are slow sections. One example is the chapter “Liturgical Detergent: Still Not Talking About the Lake” where Zach and Elizabeth discuss arbitrary topics such as “Beethoven’s Sonata no. 30” and Theodore Gericault’s famous 1819 painting, The Raft of the Medusa. Whether these sections are intentionally added to highlight the two main character’s avoidant tendencies, or perhaps these topics relate to the story’s overall message, or this is a tactic the author uses to build anticipation, these seemingly unrelated references may cause some confusion or frustration.

Lastly, the author’s use of metaphors, connecting characters to people in the Bible such as Zach comparing himself to King David, or equating Fred Valenkemp to Samson, helps one understand the characters’ personalities and foreshadows their situations. However, anyone unfamiliar with Bible may not care for these since they are used heavy-handedly. The story’s premise is church-centered, and these metaphors do help readers fully grasp its final message. Overall, Norman has produced a well-written novel that deserves a thorough read to fully absorb its concluding message about toxic religious ideals.

Jeranda Dennis is a first-year graduate student majoring in Technical Communication. She is an East Texas native with a B.A. in English Literature and a minor in International Studies.