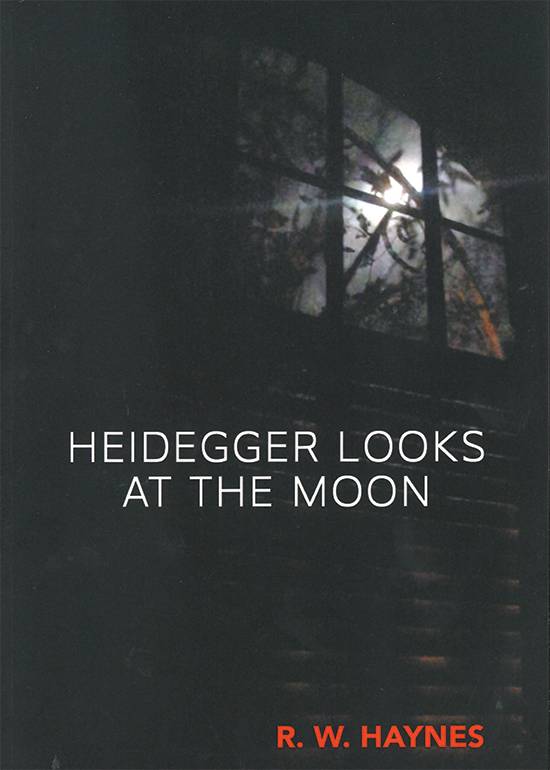

Heidegger Looks at the Moon

by R.W. Haynes

Georgetown: Finishing Line Press, 2021.

110 pp. $19.99 paperback.

Reviewed by

D.R. Garrett

“Heidegger, a German existentialist believed there was no rhyme or reason to existence and the connection of oneself to other beings was only contingent on the mental state of the individual. While reading Haynes’s poems I wondered if the feelings of meaninglessness were intended.”

R.W. Haynes’s newest poetry collection, Heidegger Looks at the Moon, is a study in Texas-style petulance tinged with Byronesque rhyming schemes that sing-song together scenes of subtropical wilderness, renegade cowboys, backyard bar-b-ques, and anti-social rants. It is no surprise that Haynes writes poetry in a classical style. A professor of English at Texas A& M International, Haynes has dedicated much of his life to the study of medieval thought, writing, and classical poetry with a focus on Shakespeare and Chaucer. His interest in classic British literature has a strong influence on his poetry.

Many of his poems reminded me of Lord Byron because of the rhyming pattern and Haynes’s obvious rejection of mainstream conservative Texas politics. In “Big Jakes Breakfast,” Haynes pokes fun at Fox-news-watching Republicans:

Out here we like our ladies cute,

Our politicians stupid, our legal code

Tailored to profit and pollute,

Comfort and Damascus are on the same road,

And all the white folks except Democrats

Are headed to Jerusalem to receive,

In another poem he goes one step further by rejecting the entire institution of mainstream American society. In “Rats of the Normal School: The Pledge of Allegiance” the portrayal of American culture is reminiscent to Allen Ginsberg’s anti-government rant “America”:

Driven not only by squealing data but by

The hounds of pusillanimity racing

Us, sold-out rats berserkly chasing

Vanishing rewards, we try and try

To grab, escape, tear loose, assimilate

Vertiginous, indigestible feasts;

And swarming like demented beasts

Around a fallen, bleeding litter mate,

Show professional designs upon success.

Haynes’s harsh criticism on American consumerism and politics may explain why he spent some of his time writing poems about non-human life. Throughout his collection of eighty-nine poems, I found myself taken back by rich images of Texas landscapes and visitations from creatures of fur and feather alike. Since much of this collection of poems is filled with so much cynicism and sarcasm, it was a nice surprise to be taken inside the imagined life of an owl. I felt as if I was transported under a fading Texas sky guided by nothing but my loneliness and the cry of a lone owl while reading “The Owl Soliloquizes a Ghostly Goodbye”:

The owl of wisdom wakes as sunlight dies,

And, as the forest fades to ghostliness,

Confidence yields as the light grows less,

And the bird of darkness eerily cries.

I wanted more poems like “The Owl Soliloquizes a Ghostly Goodbye.” The way this piece was crafted not only moved me emotionally, but the execution flowed like a clear stream after a summer rain. Unfortunately, I found myself less than moved with many of the other poems in Haynes’s collection. While his simple rhyming style was didactic and easy to read, I became lost due to the way that words were juxtaposed. As a reader of beat, slam, and anarchist poetry, I was dissatisfied by the way the rhyming pattern was executed. I wanted to see raw human experience in all its messiness spread across the page, but the only thing that seemed messy to me were the many word choices that struggled to hold my attention.

There were many strong starts to Haynes's poems but many of the closing stanzas ended without a falling action or resolution. For instance, in “Colonel Sanders Needs Love Too,” Haynes creates an alphabet soup of words that left me scratching my head by the time I finished reading the last two lines:

And as those echos blast forth distraction,

Other dramas wrap us in their charms,

Like friendly Octopi with too many arms,

Involving our minds with too much interaction.

So, we like tenacious outraged little birds,

Dodge through a storm of deciduous words.

Beyond the lack of depth and emotion was the fact the many of the rhyming patterns left me with more questions than answers. In “Ominous Sounds from the Getty Hexameters,” I get the feeling that I’m supposed to be moved by how Haynes approaches life on earth as a “Hapless Wandering.” By the end of the piece, one wonders if he is just poking fun at ritual magic or if he is actually contemplating what happens after death? Who is the Egyptian and what does he mean when he asks, “Is recovery better the disease”? Why is there grace in averting one’s face to spiritual and religious belief?

Is recovery better then disease?

Get the rooster feathers, the sacred knife,

And the gaudy gourds so we can rattle

As if anemic death’s afraid of battle,

And hides his bony face to save his bony life,

And we’ll share this poetic prescription,

Chanting lucky curses from the Egyptian

Maybe the title of Haynes’s book, Heidegger Looks at the Moon, explains the way many of his poems end with open endings and circular logic. Heidegger, a German existentialist believed there was no rhyme or reason to existence and the connection of oneself to other beings was only contingent on the mental state of the individual. While reading Haynes’s poems I wondered if the feelings of meaninglessness were intended.

D.R. Garrett is a graduate student at Texas State University.