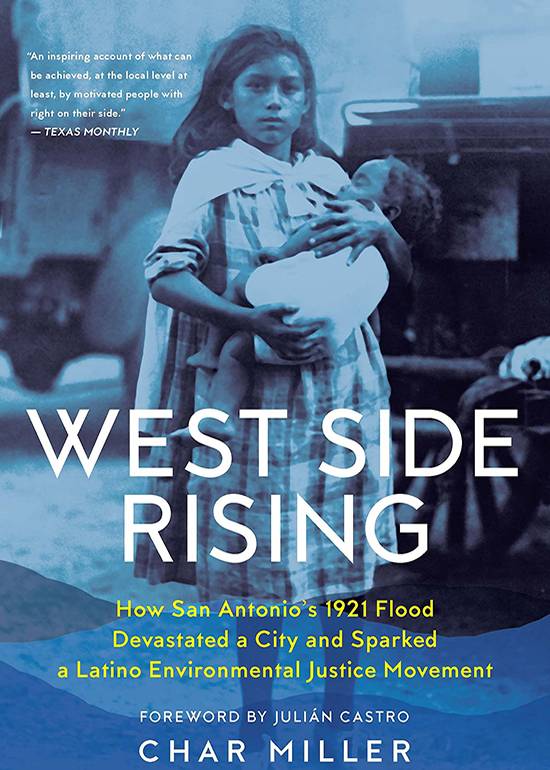

West Side Rising:

How San Antonio’s 1921 Flood Devastated a City and Sparked a Latino Environmental Justice Movement

by Char Miller

San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2021.

256 pp. $30 hardback, $20 paperback.

Reviewed by

Jason Jonathan Rivas

“The result is a well-crafted and written historical account that highlights the issues that continually plague American society: racism on a social, political, economic, and environmental scale.”

Flooding is not something many Texans remember regarding the Alamo City. San Antonio's network of dams, channels, and the River Walk has done remarkable work in mitigating flood issues, but these manmade solutions were the result of manmade problems that “made (and unmade) the San Antonio region over time.” In his book, West Side Rising: How San Antonio’s 1921 Flood Devastated a City and Sparked a Latino Environmental Justice Movement, Char Miller notes this irony through the perspectives of those affected during and after the natural disaster and those impacted by its legacy. The result is a well-crafted and written historical account that highlights the issues that continually plague American society: racism on a social, political, economic, and environmental scale.

Miller is a well-respected academic in the field of environmentalism. He taught at San Antonio's Trinity University for nearly thirty years and wrote extensively on San Antonio and environmental issues. This illustrious background is more than enough to distinguish Miller as an expert. However, his lack of social and racial connection with the people most affected by the floods put him in an “outsider” position. For some readers and scholars, his lack of physical or social connection may be off-putting. Miller, though, appears aware of this potential conflict and supports his analysis with a wide variety of primary sources, including newspaper articles, eyewitness accounts, oral histories, and correspondences. Much like the creeks and waterways surrounding San Antonio, these “insider” perspectives shape and inform the book's overall layout. He does not warp these memories to meet his argument; instead, his argument flows from these primary sources.

Miller does not bury the lead in his 1921 San Antonio Flood account. Instead, he is upfront early on and argues that the historic event was a natural disaster exacerbated by human neglect via racist policies. The victims are residents of San Antonio's West Side, a predominately working-class Latino/a community. The assailants? Public officials whose policies favored Anglo, middle to upper-class residents, and business interests. He supports this assertion via chapters that, collectively, build his overall argument. The prologue provides a backdrop of the 1921 Flood through a succinct account of an earlier disaster from 1813, based on Spanish military reports. The prologue establishes early on that San Antonio's physical location is prone to natural disasters. Why is this important? Because as Miller notes throughout the rest of the book, these memories should have informed public policy on protecting all residents from flooding, particularly the lower-income Latino/a residents living near the creeks. In truth, however, the memories would only serve those with a vested interest in the economic, social, and political circles of San Antonio.

Chapter one introduces the 1921 Flood. Miller goes into considerable detail about the death, destruction, and dire situations that flooded the city. Families washed away. Homes were destroyed. Calamity ensued as survivors and witnesses battled for their lives. In the flood's aftermath, city officials responded by creating an artificial memory of the disaster by underreporting casualties and damages while focusing their rebuilding and mitigation efforts on the affluent parts of the city. City leaders wanted the world to see a quickly-rebounded San Antonio open for business. For the residents of the West Side, though, public policy neglect became the status quo for the next fifty years.

The rest of the book presents different organizational responses to the 1921 disaster and how San Antonio reacted to said organizational responses. Chapter two concerns the American Red Cross and its efforts to prepare for the impending floods and their remarkable response to the ordeal. While the Red Cross would help thousands with short-term aid, Miller provides primary source correspondences between the local and national chapters that privately show how racism factored into who deserved the assistance.

Chapter three concerns the army’s response to the disaster. San Antonio's position as a major military city helped it mitigate the impact of the flood in the short term and provide a blueprint for how to prevent a similar occurrence in the long term. However, the behind-the-scenes maneuvering of city officials illustrates how even the army was not immune to political corruption. The following chapter concerns the city finally responding to the aftermath of the flood. A new political leader and vision brought new flood control measures to the city. These actions created a sense of promise for the beleaguered residents of the West Side. But, as Miller points out in chapter five, the city's response to potential natural disasters continued to favor the economically, socially, and politically advantaged. The final chapter tackles the rise of grassroots organizations and political leaders who forced the city to address the interests of the West Side. As Miller notes, "Nature, the source of so much death, damage, and disarray on San Antonio's West Side, had become the catalyst of its resident's liberation..."

West Side Rising is an important history book. It is an in-depth analysis of events that culminated in the historic 1921 flood, a breakdown of the event, and its aftermath. Miller is sometimes dense when dredging through the channels of information and statistics. However, his use of photographs and newspaper clippings helps readers refocus on his narrative style. Additionally, many parts of the book are quote-heavy, creating a complex situation where multiple storytellers are on the same page(s). This practice, intentional or not, allows Miller to guide the narrative while providing agency and power to the flood’s victims. By relying extensively on quotes and primary accounts, Miller shares his platform with the "insiders" who experienced 1921 firsthand and gave credence to Char Miller's central argument: that natural disasters coupled with systemic racism begat the environmental and civil rights movement in San Antonio.

Jason Jonathan Rivas, of Houston, is a graduate of Texas State University’s History Graduate Program, specializing in Public History. His thesis concerns the public memory of WWII through Hollywood films. He works at the Texas Department of Transportation as a historic preservation specialist.